RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECT ©2013 . All rights reserved

Article Details

Photography: RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECT

Architect: Brininstool + Lynch, Chicago

Brad Lynch (lead designer); David Brininstool, AIA (managing principal); Dan Martus (project manager); Dena Wangberg (project architect); Joice Krysak, Eirik Agustsson, Hillary Hyson (project team)

Mechanical Engineer: AA Service Co.

Structural Engineer: Goodfriend Magruder Structure

Electrical Engineer: Dexter Electric Co. Civil Engineer Moshe Calamaro & Associates

General Contractor: Goldberg General Contracting

Landscape Architect: Coen + Partners

Source: RESIDENTIAL ARCHITECT | View original article

Share this Post

In the client’s mind, it all began with a warehouse.

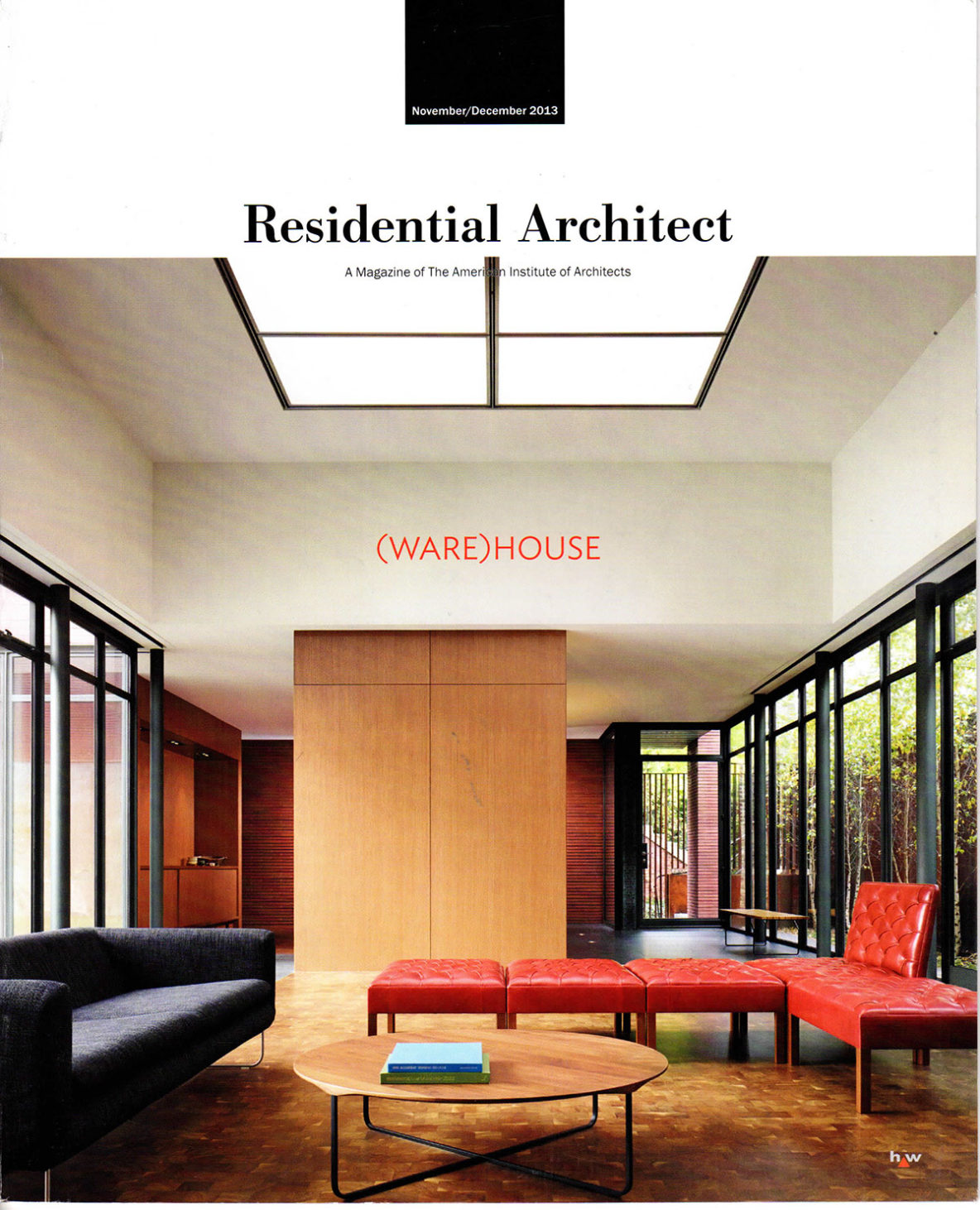

The high-powered businessman wanted to find a warehouse and convert it into a home. He wanted to keep the industrial building’s roughhewn edges and materials-metals, wood, concrete, copper-expressed and exposed, while still making it welcoming. And he hired Brad Lynch of Brininstool + Lynch for the job.

But finding the right warehouse, or former industrial building, proved a tall order in Chicago’s Bucktown neighborhood. More than 20 years of gentrification had claimed-by condo or demo-many of the suitable buildings that were once easily found there.

Lynch had a solution: Rather than converting an old buildingespecially when no one knew if the right one would ever come alongwhy not design and build an entirely new and contemporary house, using the same mix of materials found in an industrial structure?

During dinner with his client, Lynch turned to the proverbial napkin sketch as a method of persuasion. (“I sketched it out on the back of a placemat covered in tomato sauce” Lynch says. “He says he’s still got it somewhere:’) And the client was sold.

In the final house, which was completed in August, behind a Cor-Ten steel fence on a Bucktown residential street, it’s all there: brick, weathered copper, steel. But the industrial package is bundled in a refined and sophisticated urban architecture where the materials, their texture, and their beauty are simultaneously subdued and boldly let loose. The materials aren’t just tacked-on; they help give the building form, character, and function.

The home is also sustainable; it’s efficiently heated and cooled with geothermal systems beneath the landscaped courtyard. Mechanical window shades shield and permit sunlight to passively heat and cool the home when needed.

In the following Q&A, Lynch talks about the three-year journey to get the house built.

Were there any complaints from the neighbors or officials about the building?

Because even though it uses the same materials, it looks physically different than what’s around it?

No, if you really examine the neighborhood and the lots and houses that are there, most of them are nonconforming. Some of them are wider than others. Some of them are taller than others. Some are built of different materials.

If you were to have a panoramic view of the block it would be truly disparate in terms of the time these buildings were built, the materials that were used for them, what the aesthetics were, and the size of the lot. This obviously is a contemporary response, but actually uses traditional materials that are not in conflict with what’s in the surrounding area.

One of the first elements you see is the slatted fence, made out of Cor-Ten, which is a popular material in Chicago. How did you select it?

Well, the landscape architect really designed it, and both the owner and I got to give input in terms of where we went with it. And I think we all agreed that the look of Cor-Ten would be really inappropriate for the neighborhood; it seems like it just belongs as an urban-material element.

We picked where those slats would be more open and more private based on where the owner wanted to see out. You get a sense of openness, but you can’t really see in. There’s a sense of anticipation.

How did the house’s street presence develop?

We really wanted the fapde to be a composition, more than an idea of window placement. In the city, everybody has their blinds or drapes drawn. In this house the light goes through, they get the sense of light and sky, but the composition allows it without having to pull the shades.

There’s the great copper element. There are other industrial metals you can use-aluminum, for example. But the copper is what we see. Why?

The client really wanted copper, and he wanted it pre-weathered. We didn’t want it to look like anything else, so we spent a lot of time studying this pattern, which is not sequential. The closer you get to it, the more interesting it becomes; it’s not just the openings, which are larger in certain areas than others, it’s the embossing of the material. It has some life to it.

What about the courtyard and this relationship between inside and outside?

It really began with these three lots, and then saying, well, I don’t need a house that covers the whole property. A lot of the square footage in this house is not about habitable space; it’s about how it works with the site.

In a northern climate like this, having the ability to experience the outdoors from your living space, no matter what time of year it is, is a luxury. It’s like having your own park. And so to emphasize that, rather than de-emphasize it, copper panels move in and out of the space, the granite is the floor for both the circulation outside as well as the circulation inside, and there is really no solid between. One works with the other.

Now that he’s there, is the client convinced?

It’s great. This is our fourth project with this client. But even so, it’s very difficult to sell something to a client that is not in their reality. If you can’t point to it and say this is what it’s going to be, this is what it feels like, and this is what it’s going to look like, they have a hard time imagining it-no matter how you model it. And so there is a trust factor.