Source of Article ©2010 Custom Home. All rights reserved

Article Details

Photography: Robert Tolchin; Steve Hall/Hedrich Blessing; Christopher Barrett; Barbara Karant/Karant+Associates; Ferguson Photographic, Chicago

Architects: Farr Associate, Chicago; DeStefano Partners, Chicago; Vinci | Hamp Architects, Chicago; Brininstool + Lynch, Chicago; Wheeler Kearns Architects, Chicago, and McGuire Igleski & Associates, Evanston, IL

Builder: Goldberg General Contracting Inc

Source: Custom Home Online | View original article

Share this Post

The Natural

Jake Goldberg pursues his true calling.

Custom Builder of the Year By Bruce D. Snider

If one were to design a curriculum for aspiring high-end urban custom builders, it might look a lot like Jake Goldberg’s life. His father, who had studied at the Illinois Institute of Technology in the 1950’s under Mies van der Rohe, ran his architecture firm out of the family’s stately brick Victorian in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood. His mother, an interior designer, also worked at home. By the time Goldberg was in high school, he was drafting in the home office off the big oak-paneled entry hall doing carpentry on the houses his father bought and renovated. He studied economics and finance at the University of Illinois, but a construction career seems never to have been in doubt. “When everyone else was running around and confused about what they were going to do,” says Jeff Berry, Goldberg’s lifelong friend and company vice president. “Jake was born with a hammer in his crib.”

The fact that he was born in Chicago adds to Goldberg’s pedigree. Home to Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies, and other giants of the profession, “Second City” is America’s first city of architecture. It was the Chicago School architects of the late 19th century-Sullivan, Henry Hobson Richardson, John Wellborn Root, and others-who laid the groundwork for the European-bred modernism that would flourish here a half century later. Chicagoans can name not only their landmark buildings, but also who the architects were, and the city supports a community of residential modernist architects as vibrant as any in the country. “I remember being a kid and having my father point out architectural gems of the city,” Goldberg says. As a builder he has come to play an active role in preserving the legacy of Chicago’s past masters and furthering the work of the contemporary architects who are in their stylistic and spiritual descendants.

None of this happened overnight, of course, “I started Goldberg General Contracting in 1987,” says the builder, now 44. Then fresh out of college, he began with the kind of small projects he had done in his spare time since high school. Berry remembers those days with some amusement. “You always knew it was Jake coming,” he explains. “He had this Econoline van that was the nastiest thing you’ve ever seen. Jake, what color was that original van you had?” Goldberg answers with a trace of nostalgia: “Light blue, with an orange door.”

Before long, Berry was riding in the van as well, having joined his friend in the spec rehab of a three-flat apartment building. “Jake literally loaned me the tool belt, “Berry remembers. “We had no money,” Goldberg adds, “so we did everything ourselves: demo, plaster, siding, everything.” When the job was done Goldberg moved into the building, the company set up shop in the basement, and the partners moved on to the other projects. The recession of 1990-1991 made further spec renovation unprofitable, so it was back to the kitchens, baths, and basement build-outs. “But there wasn’t enough money to support two principals,” Goldberg says, so the pair split up amicably and Berry moved on to a project management job for a real estate developer.

Goldberg, too, had had aspirations as a developer. But even as a young man, his low-key confidence made him well-suited to custom building-and to building a business. As the projects he took on grew in size and complexity, he kept his company lean, handling all sales and project management himself. He knew from experience in the field that there were certain items over which he wanted to maintain control. Even today, he says, “We really feel we have to self-perform all our carpentry and metalwork, for quality and efficiency. We’ve tried subcontracting out the tilework from time to time, and you just can’t.” Smooth, uniform grout joints, clean welds-”A viewer may not be savvy enough to see all these things, but it will really make a difference in the impact of the building,” he maintains. “That’s the subtlety you’re trying to convey when you’re convincing a client to hire you.” If those sound like the words of a man who views building as more than a means to financial end, Goldberg readily confirms it. Somewhere along the line he says, “I realized I loved building. I lost interest in the development part and just focused on building.”

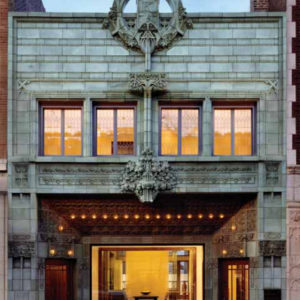

That focus sharpened and took on a distinctly local cast wehen Goldberg made the acquaintance of two prominent Chicago architects-one long dead, the other very much alive. Friends of a friend had purchased the Gold Coast house of John Wellborn Root (where the architect lived while he planned the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the fair that heralded Chicago’s rebirth after the 1871 fire), and Goldberg General Contracting (GGC) became its unofficial caretaker. “I’ve worked on it for 18 years,” says Goldberg, who repaired, restored, and added to the house. Recognizing their home’s historic status, the owners also retained Vinci | Hamp Architects, as a Chicago firm known for its expertise with historic buildings. Suddenly, “I was working with the foremost preservation firm in the city,” says Goldberg, who remembers the experience as “pivotal.” In time, he struck up a friendship with firm principal John Vinci, who had been an architecture school classmate of his father. The older man thought highly enough of Goldberg to hire his company for work on his own house and came to trust Goldberg with even his most demanding clients.

“He has a natural sense of quality, there’s no question about that,” says Vinci, who adds that Goldberg brings more to the table than just technical ability. A thorough appreciation of architecture is part of the equation too. “We speak the same language,” Vinci explains. “He gives people books on architecture for Christmas, and he goes to the trouble of finding the best, most current ones. He has a real heart for architecture.” And Vinci’s mentorship did more than expose Goldberg to the history of Chicago architecture; it placed him in the living stream of it. A lifelong champion of architectural preservation, Vinci is an unapologetic modernist in his own work, and his projects often reflect both of those passions.

One such project occupies the penthouse floor of a turn-of-the-century brick apartment building by the architect Howard Van Doren Shaw. Greeting the building superintendent by the first name on the way through the lobby, Goldberg explains, “This was the first co-op in the world.” Shaw’s own apartment-a 5,000 square-foot gem with views over Lake Michigan-now belongs to a couple with significant pre-Columbian pottery and contemporary art collections. Reflecting this dual aesthetic, Vinci’s program included both the painstaking restoration of an oak-beamed, limestone-paneled dining room and the gut remodel of the original servants’ quarters into a strikingly modern gallery area, guest quarters, and master bedroom suite. “That was a quintessential job for GGC and Vinci,” Goldberg notes, “because you have the merging of historical sensitivity with modern design.”

By the late 1990’s, the ability to handle these two most demanding disciplines-as well as to navigate the urban labyrinth of permitting authorities, hypersensitive neighbors, and hyper-vigilant building superintendents-had put GGC on the radar of the city’s foremost residential architects. And Goldberg found himself at another turning point. “I was in a really good place, where I had a [sizable] workload,” he says-more than he could handle by himself. “I knew I needed a project manager.” enter (or re-enter) Berry, who had spent the intervening years honing his project management skills on multifamily projects of increasing size and complexity and was looking for a change. Berry’s return a project manager/vice president boosted GGC’s already steep upward trajectory. “We went from maybe eight guys to about 20,” says Goldberg, who had recently bought a larger building to house the growing company. GGC crews remodeled the office space in a sophisticated minimalist scheme of Goldberg’s design, further bolstering the company’s credibility with architects.

Goldberg and Berry meet with their five site managers every Friday at 7 a.m. in the office’s glass-walled conference room to review the current week’s work and plan for the next. “We schedule on this flat-panel with Excel,” says Goldberg, pointing to a large wall-hung monitor. “We bring up problems we’re having and share suggestions about how to avoid pitfalls and do things better.” The company captures that collective wisdom in its “Site Manager No-Brainers,” a living document now 12 years in the making. Goldberg calls it “a running list of construction management fundamentals, the things we’ve learned to do and not to do.” At the monthly meeting of all 25 field employees, each site manager makes a presentation on his current project, often supplemented with on-screen photographs or video. “I also assign people topics to present on,” he says, noting that there’s a waterproofing detail book he especially likes. “I’ll give that book to one of the guys and ask him to pick an article to present on.”

The goal of these informal training efforts is to the distribute expertise throughout the company. “We reach back to the staff to learn how we can do things better,” adds Goldberg, who invites criticism from his employees-sometimes to the point of insisting on it – and eagerly supports those seeking new skills. “If you want to learn to set tile or do metalwork, we’re glad to teach you. There are a lot of opportunities to bounce around.” The proof of the system, in addition to the company’s low turnover rate, is in the quality and service the company delivers. And those in the best position to judge are the architects who have worked with GGC over the years and, in several cases, have chosen the company to build their own houses.

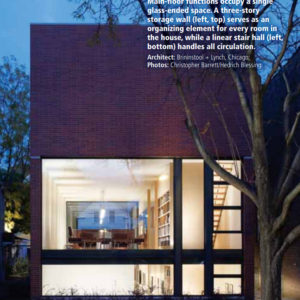

Among the latter is Brad Lynch, of Brininstool + Lynch, whose own GGC-built house earned a 2008 Distinguished Building Award from AIA Chicago. A radical exploration of those possibilities of the standard Chicago urban lot, Lynch’s house takes the form of a glass-ended, oblong box. “These are the biggest residential windows in the country,” says Goldberg, noting the 10-foot-by-14-foot, 2,500-pound glass end walls of the great room, which stretches the full depth of the building. The tubelike building section required three steel moment frames, and the house’s long, unbroken interior surfaces demanded virtual perfection in execution. Lynch says that when he builds a house outside of Chicago, he looks for a commercial builder. “A residential contractor will look at our drawings and not even know what they’re looking at,” he says. “Back home in Chicago there are a number of high-end residential contractors who can handle this kind of thing, and Jake is one of them. I’ve worked with him for a long time, and he’s gotten better and better.”

Positive regard among architects gets GGC on the bid list (which has allowed the company to avoid layoffs and maintain its business model in the current recession), but Goldberg is leveraging it to bypass bidding entirely. On the Vinic apartment job, he reports, Vinci said, “We want to work with Goldberg. GGC is going to be the contractor.’ That’s the ideal kind of project for us. It’s all about trust and who we’re working with, rather than who’s the lowest bidder.” It also gets the company in at the planning stage, when its value engineering input does the most good. But even with clients who are reluctant to go to construction without a bid, GGC’s connections can get it in on the ground floor with a paid consulting relationship during design development. “It gives the architect and client a chance to get to know us, see what we bring to the table, develop a level of trust,” Goldberg explains. “And by the time we get to the bid process, we have the upper hand.”

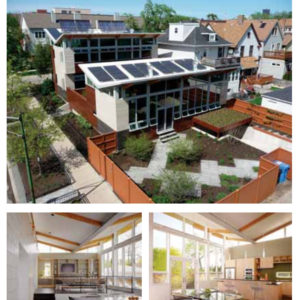

A recent high-profile project illustrates the potential of this kind of relationship. A client had approached Chicago architects Farr Associates with the audacious proposal of building the greenest house in the country. LEED Platinum. Net-zero energy use. In Chicago. At Farr’s invitation, GGC contributed feedback on the design virtually from the schematic stage. “The LEED Platinum tag was something that [the owner] really wanted,” says Berry, who managed the project, and the zero-energy requirement “was making that very difficult to accomplish within his budget.” Berry crunched the numbers and specs with Marvin Windows and Doors to hit his solar, thermal, and cost targets. Also factored into the cost/performance equation were a geothermal HVAC system; rainwater collection, filtration, and storage, photovoltaics; solar hot water; and a graywater system that uses filtered laundry water to flush the toilets. “Part of our education here was bringing our subs up to speed,” Berry says. (And not just the subs. When the city inspector saw the graywater system, he advised the plumber to “run for the hill.”) Our challenge was to take all that and still build an architecturally significant project.”

In Goldberg’s view, building Chicago’s greenest house puts GGC out in front of what could be a significant shift in the custom home market and may represent the logical next step in the development of his company. As with every threshold event, it offers a moment for reflection. And looking back, even Goldberg is struck by the arc of his career. He notes his good fortune in growing up surrounded by great buildings “and later having the responsibility of doing a major restoration” of one of them. Now, after tending to the works of Sullivan, Wright, and Mies and bringing to life some of the finest work of the current generation of Chicago architects, he is producing buildings that may well set the standard for the generation to come.

Jake Goldberg may have been born to build, but even he couldn’t have known how far he would take that-or how it would take him.