Source of Article ©2008 Architectural Record. All rights reserved

Article Details

Photography: Elizabeth Fellicella, Hedrich Blessing, Hisun Wong/China Heritage Fund, @ Steve Hall/Hedrich Blessing, Except as noted: American Terra Cotta Company Records, Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries

Architect: Wheeler Kearns Architects (adaptive reuse) – Larry Kearns, AIA, principal; Sharlene Young, AIA, project architect

Architect: McGuire Igleski & Associates (facade restoration) – Anne McGuire, AIA, principal in charge

Architect: William Presto with Louis H. Sullivan (original building design)

General Contractor: Goldberg General Contracting

Source: Architectural Record | View original article

Source: Architectural Record (photos) | View original photos

Share this Post

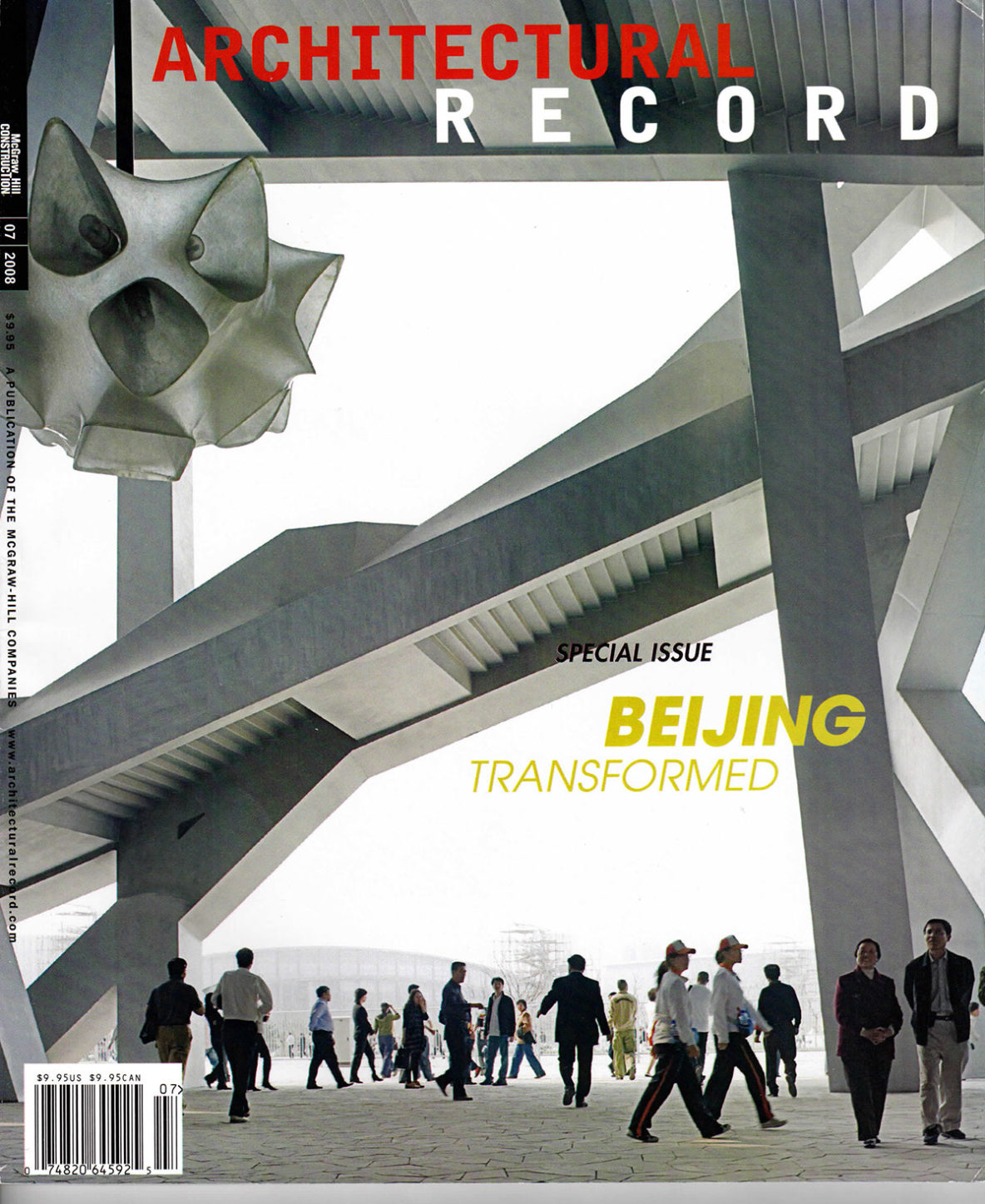

ADAPTIVE REUSE

Dialogue in time

When architects deploy space, light, and materials to bring modern design into historic structures, the concretized shifts between moments in time can be perceptually arresting.

By Suzanne Stephens

Most provocative examples of historic preservation make us aware of the past and future as a shifting continuum between moments in time. A magazine that consistently investigates this preservation thesis, Future Anterior, was found in 2004 by its editor, Jorge Otero-Pailos. It appears semiannually under the auspices of Columbia University’s graduate architecture program in historic preservation and is published by University of Minnesota Press. The phrase “future anterior” derives from the French term for a verb tense-with Jacques Derrida’s much-cited use of it providing additional inspiration. Most simply put, it describes an act that will have been accomplished at some designated moment in the future. Arguably, when a historic building is preserved and transformed for new uses, the dialogue created between old, conserved, or restored elements and the newly modern brings these shifts between past and future tenses into a dramatic present. Architects who effectively manipulate space, light and materials to suggest something about the future beyond the process of time embodied by the historic remains help to perceptually thrust the observer both backward and forward from the present moment he or she experiences this architecture.

At the Diane von Furstenberg Studio Headquarters in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, Work Architecture Company (WORKac) exploits the difference between the historic brick warehouse and its interiors by introducing a central glass-and-steel stair, topped by a large angular yet bulbous skylight. The dialogue created between the vernacular, industrial exterior and the light-filled, open interior unites and highlights the time warp between the two.

In the case of the Krause Music Store in Chicago, one of Louis Sullivan’s last commissions, the conversation is much quieter. Here Wheeler Kearns Architects creates a spacious, calm, and linear interior within the diminutive Sullivan structure whose facade has been restored sensitively by McGuire Igleski & Associates. The effect is not one of dramatic contrast as much as the discernible and elegant evolution of a proto-Modern vocabulary to an updated Modern one.

In the third example, with the reconstructed Jianfu Palace Garden in Beijing, the structures conscientiously reproduce the drenched colors and the surfeit of ornately carved ornament of the 18th-century original. The interiors, on the other hand, by Tsao & McKown and Pei Partnership, offer an expensive design and architecture of spare forms, exposed structure, and muted colors, dramatically counterpointing the intricately re-created exteriors.

Two: KRAUSE MUSIC STORE

CHICAGO

Wheeler Kearns and McGuire Igleski restore Louis Sullivan last work to its former luster and create a serene work space within.

By Joann Gonchar, AIA

Size: 4,400 square feet

Cost: Withheld

Completion date: 2007

Sources

Terra-cotta restoration: Grice Building Maintenance; Erin McNamara

Secondary glazing: Allied Window

Interior glazing: Bartlett Shower Door Company

Fabric scrims: Knoll Textiles, Zirlin Interiors

Interior ambient lighting: Pinnacle, Light Lab

Millwork: Stay-Straight Manufacturing

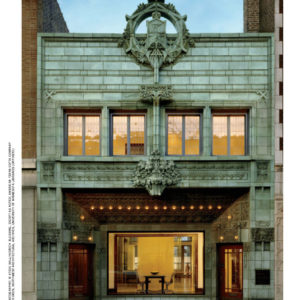

The two-story storefront at 4611 North Lincoln Avenue on Chicago’s North Side may not be Louis Sullivan’s highest-profile commission, but its delicate ornament and graceful proportions certainly reveal his skillful hand. The focal point of terra cotta facade is a deeply recessed, proscenium like display window. From its lintel, a leafy profusion of ornaments extends, ending in an elaborate cartouche that projects above the parapet and surrounds a letter K.

The initial refers to William Krause, who commissioned architect William Presto in the early 1920’s to design a music store with living quarters above. Presto in turn hired Sullivan, by then elderly and plagued by financial difficulties and poor health, to design the facade. The store, which opened in 1922, was Sullivan’s last architectural project-he died less than two years later.

The program

The music store occupied the ground floor for less than a decade before Krause rented it to a funeral home. The building contained a gallery and gift shop in 2005, when nearby residents Peter and Pooja Vukosavich acquired the structure with the idea of moving their marketing and communications business within walking distance of their home.

But the former music store was more than a convenient locations for the Vukosaviches. They had long admired the structure and hoped to help ensure its preservation. The city had designated the facade a Chicago Landmark almost 30 years earlier, but the couple wanted further protection for the building. So soon after completing the purchase, they began the paperwork for placing it on the National Register of Historic Places (a status it achieved in 2006).

Solution

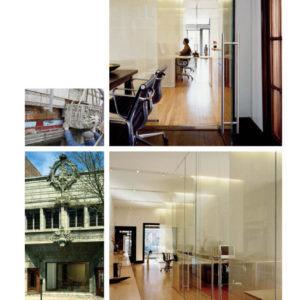

The Vukosaviches selected Wheeler Kearns Architects (WKA), a local firm with the reputation for carefully detailed designs, to transform the building into an office. For WKA, the landmark designation meant not only maintaining Sullivan’s elevation, but also paying special attention to sight lines through the facade into the zone immediately behind it.

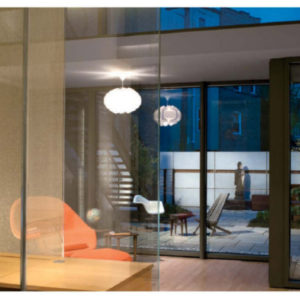

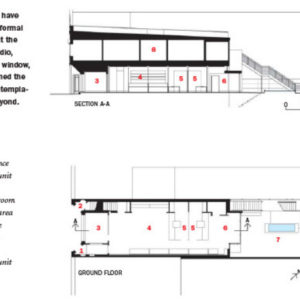

The architects’ strategy included converting the display window (originally designed to accommodate a grand piano) into a conference room, and inserting the rest of the program in the long and narrow space beyond. They consolidated stairs, office equipment, and other support functions along the office’s northwestern edge, and then used six fabric scrims as the primary organizing elements. The gossamer partitions, separated by a dimension equal to the depth of the display window, “echo the conference room dimensions and reinforce the symmetry of Sullivan’s facade,” says Sharlene Young, AIA, Wheeler Kearns project architect.

The scrims veil the activity of the studio from the passerby but allow a visual connection among staff members, who occupy open workstations, and the two partners, who have floor-to-ceiling, glass-enclosed offices. The gauzelike elements also establish a rhythmic progression from the busy street to an informal work space at the rear of the studio. Here the architects have opened an enclosed back wall to views of a contemplative garden.

At the facade, the restoration strategy was to retain, rather than re-create, its historic fabric. For example, the team decided against replacing cracked terra-cotta, adn instead elected to perform so-called “bench repairs” by removing broken units, gluing them back together with epoxy, and then reinstalling them.

Preservation efforts involved not only the decorative surface of Sullivan’s elevation, but also the structure beyond. Preliminary facade investigations indicated deterioration in the steel lintel above the second-floor windows. And once workers removed terra-cotta from this area, the extent of the damage became clear. “We could see the interior lath through the web,” says Anne McGuire, AIA, principal in charge of the projects in and around Chicago.

Despite the severity of the deterioration, the project team opted to reinforce the steel section in situ because its replacement would have required further disassembly of the facade and damage to still-intact tiles. “It would have been highly invasive,” says Jake Goldberg, president of Goldberg General Contracting, Chicago, the construction firm for both the facade and the interior work.

Recognition of the facade’s cultural and aesthetic value was the key factor behind the goal of maintaining its original components. However, the environment was also a concern. In particular, the designers were keenly aware of the building’s embodied energy, or the energy required to manufacture and install its original materials, says McGuire.

In addition, both architecture firms saw the opportunity to improve building systems and the exterior envelope. They took such sensible measures as specifying energy-efficient lighting for the interior, installing high-performance glazing at the rear bay window, and designing storm windows that would not obscure the intricate and newly restored cames of the second-story windows.

Commentary

If this project has any flaw, it is that the fabric scrims are so ephemeral as to seem almost temporary. However, they imbue the interior with a Zen-like calm-a calm that seems well-suited for a collaborative and creative work environment and provides the perfect complement to Sullivan’s carefully restored facade.

The architects have provided an informal seating area at the rear of the studio, and with a bay window, they have opened the space to a contemplative garden beyond.

Office entrance

Residential unit entrance

Conference room

Open office are

Private office

Seating area

Garden

Residential unit