On the western shores of Lake Michigan, a composition of brick and stucco, leaded glass windows and overhanging eaves, emerges from its sloped landscape in an artful celebration of geometric abstraction. Surrounded by planted sumac and prairie grasses on a blufflike dune ecosystem, the home is respectful of the iconic Prairie Style where principles are adapted for its site, purpose, and time. There is an integration with its landscape as its rectilinear form intentionally wraps around a150-year-old oak tree and opens out toward the lakefront in an expression of waterfront living. Its simple, natural palette celebrates the discipline of ornament and artistry of craftsmanship from artisan tiles and hand-carved autumnal friezes to clerestory windows allowing light to illuminate the interior, emphasizing its connection to the outdoors.

From the street, there is a reminiscence of the deep-set, mullion-leaded windows and contained, cubic masses of Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Emil Bach House, while the landscaped backyard and planted sumac evoke the stylized vocabulary of the Dana-Thomas House in Springfield, Illinois. But as it unfolds onto the dramatic grade of the site toward the lakefront, the estate is a symmetrical composition of Prairie Style inspiration, tiered terraces, and landscaped oasis that speaks an expressive dialect uniquely designed and built for its owners. “We like to do contemporary work and interesting modern work, but it seems like our niche is learning from the past and designing for the future. We look at precedents, we look at past examples that we find are classic and great examples of architecture, and then we try to distill that into a new vocabulary and take that and bring it into today’s standards and the way people live today,” said Scott Fortman, AIA, LEED AP, principal and president of Gibbons, Fortman & Associates in Chicago, Illinois.

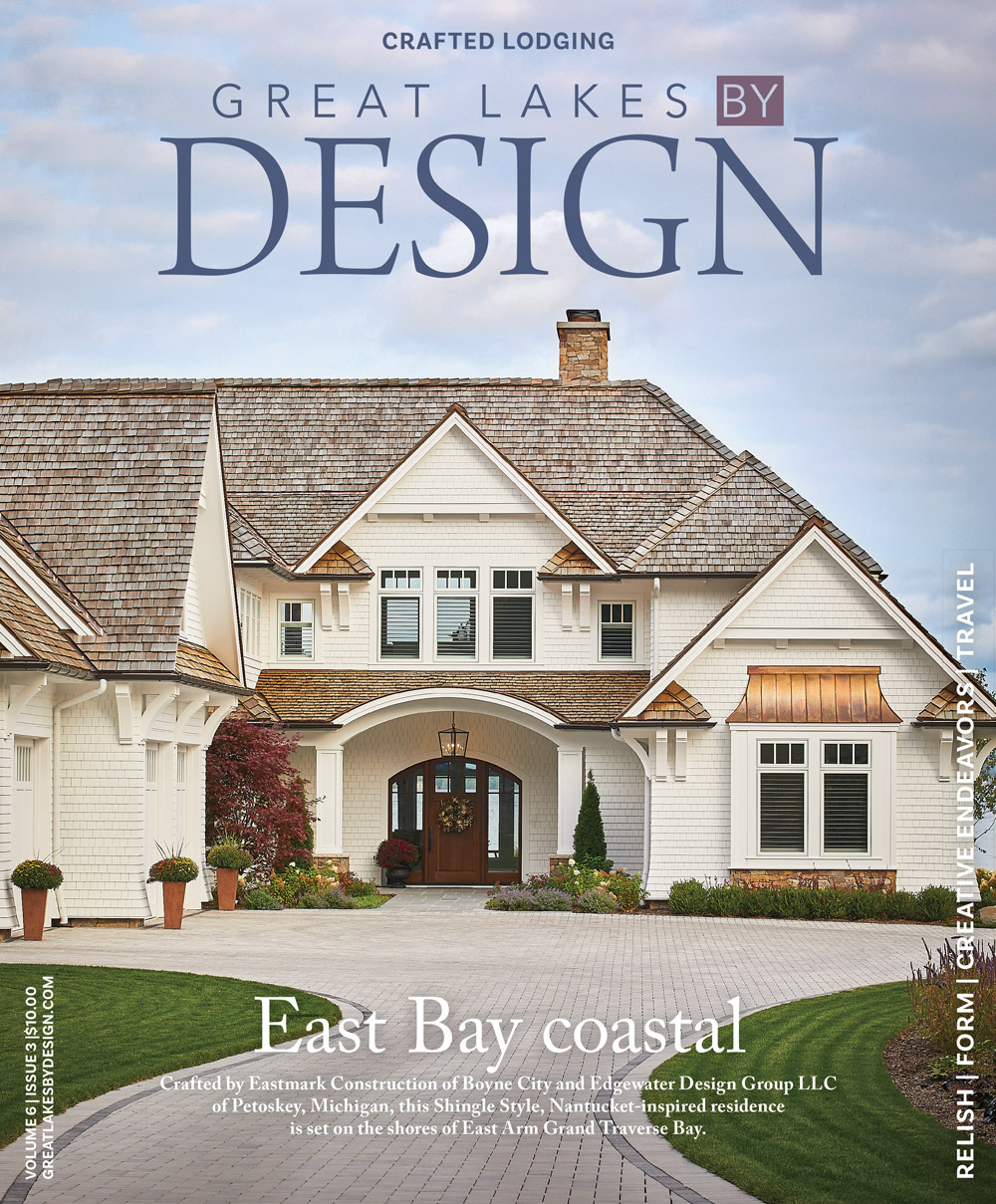

“The old houses we use for references just don’t work when it comes to a layout—the kitchens and the way people live today more informally—so we take these standards and lessons we have learned from history and from some of the best precedents and try to bring that into the 21st century,” Fortman added. Gibbons, Fortman & Associates is an award-winning architectural firm specializing in both residential and commercial work with locations in Chicago, Illinois and Naples, Florida. The firm offers a range of renovation and new construction services such as architectural, interiors, kitchen and bath, furniture and selection, and schematic design, among others, as it works across different architectural vocabularies to create well-proportioned structures and interiors of graceful detail tailored to their clients.

Initially founded in 1990 by Richard Gibbons, AIA, as Richard Gibbons & Associates, the firm has since developed into Gibbons, Fortman & Associates with Gibbons serving as partner emeritus and design consultant, and Fortman assuming leadership of the team after serving as project architect for nearly a decade and principal since 2000. “I think most architects become architects, because they want to design something unique. For me, I think architecture should be inspirational,” Fortman said. “It’s inspiration. People don’t hire architects because they just need a roof over their heads; they want something that is going to inspire them every day. They wake up and walk through the house and go, ‘oh my gosh, this is incredible.’ That is my goal, to create something that is special and people love it and when I walk away and am done, I go, ‘wow, I love that house.’”

The firm, which has a portfolio of work ranging from French Renaissance and BeauxArts to Arts and Crafts and modern inspiration, first took on the distinctive architectural language of Prairie Style more than a decade ago when designing a residence in Crete, Illinois inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wingspread. Fortman noted it was after seeing that project combined with a number of referrals that the clients of this roughly 15,000-square-foot beachfront residence reached out to the firm to help realize their vision.

“I have always been a fan of Prairie Style and Frank Lloyd Wright. It is probably the reason I got into architecture in the first place. He really brought residential design to a new level back 100 years ago. We had done a project for a client maybe 10-to-15 years ago who had come to us and said, ‘I want to do a Prairie Style house,’ and I said ‘oh, I can do that,’” Fortman said. “They thought it was one of the best true-tothe-original Prairie Style [homes]. We tried to get all the details correct and tried to make sure we were not just mimicking the basics of it, but really getting the materials, the techniques, and things like that correctly. You know, that is the best kind of project when you have a referral plus people see your work and like it,” Fortman added. Brought in early on in the process, Fortman said it was really important for the firm and the clients to have a team that worked together when addressing the site with its existing home and integrating Prairie Style principles in a cohesive manner from landscape and exterior façade to interior structural details. The team not only featured interior designers and audiovisual consultants, but also landscape architect Craig Bergmann of Craig Bergmann Landscape Design Inc. of Lake Forest, Illinois, and Goldberg General Contracting Inc. of Chicago, Illinois.

Founded in 1987, Goldberg General Contracting specializes in new construction, restoration, and renovation in both custom residential and light commercial, with an expertise in modern design. Throughout the years, the firm has also been recognized by Landmarks Illinois and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for its restoration work and has experience working on projects designed by architects such as Louis Sullivan, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Howard Van Doren Shaw, and John Wellborn Root. The company, which comprises a team of highly skilled craftspeople, tile setters, site managers, and more than 25 carpenters, also partners with licensed subcontractors and numerous architects and interior designers throughout the greater Chicago region. Jake Goldberg, president of Goldberg General Contracting, said the site itself was a big part of the story of the project for the team as an exceptionally deep site at more than 800 feet from street to lake with a grade change of about 25 feet across a couple of different ecosystems. “There is a dune ecosystem that transfers to more of a beach. There is a central zone of large cottonwood trees and a recess garden area that then transforms into sand dunes that are a mix of grass and dune and then beach. There was a pre-existing home that was built right into the bluff where the table land meets the lower dune area,” Goldberg said. “So, there you have an interesting engineering challenge, because you are moving from very dense, hard native clay on the upper side of the table land to pretty much all sand as you get to the bottom of the bluff.” Though the eventual footprint of the home would come to straddle two different soil conditions—and excavation after demolition of the existing residence would unearth fill material often used in the ’60s and ’70s to expand the table land, requiring engineered crushed stone to be brought in to achieve a certain loading requirement—presented its own unique set of constraints, Goldberg noted the clients were very respectful of the natural condition of the site. “We built the new house around a huge oak tree and it became the centerpiece of the drive court and the building itself. During construction, we had to be very respectful of the roots and protect them and keep the tree watered and make sure that the digging, heavy equipment, and trucks going across the site didn’t damage the roots,” Goldberg said. “We actually worked with civil engineering and the landscape architect to create a special mat that is made out of a web of plastic and stone to distribute the weight of the heavy machinery so as to not damage the roots and when we put in the snowmelt for the driveway, we omitted it from the zone where the tree roots were, because the snowmelt, radiant heating, can adversely affect the tree,” Goldberg added.

It is an intention that is reflective of Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision of organic architecture and an emphasis on nature, where the design of a dwelling is an artistic expression of both landscape and its dwellers. Fortman noted some of the main ideas both the firm and the clients liked about the Prairie Style was that connection to the site and the relationship between environments. Though the property is a sloping lakefront site as opposed to the expansive prairie landscape that initially inspired the horizontal bands and linear lines of Prairie Style, Fortman said they adapted some of the principles of the style to suit the site, integrating retaining walls and stepped terraces, since how a home fits into the site is an important element of Prairie Style. “The clients really wanted to get a natural landscape so we did use a lot of prairie grasses and it was important to the clients to return the site to be as natural as possible, as if it had always been that way and not something that was contrived or sort of stuck on the site, but something that married with the existing conditions,” Fortman said.

The solution was to thin out some of the trees that weren’t native, plant prairie grass and sumac—a material popular with Frank Lloyd Wright that eventually became a signature plant used in Prairie Style gardens—and integrate planters with cascading vines into the house as well as on the exterior to soften the architecture as the plant grows up the walls. Some of the other principles integral to the design comprised leveraging a simple palette of materials such as brick, stucco, limestone, and clay tiles on the roof with cedar trim that was then reflected in the interior in an intentional blurring of lines from building to landscape. Fortman noted the team also designed approximately 70 leaded glass windows whose pattern was inspired by and in reference to the oak trees the home itself was designed to wrap around. Each window features an oak tree complete with an acorn at the bottom with the stylized pattern sprouting out of it, which is also reflected in the carved friezes of an oak branch, leaves, and acorns that flank the entrance in more of a nod to the Arts and Crafts movement.

“We brought some elements of Greene and Greene or some of the California architects where they did a lot of hand carving and basrelief details. That is one of my favorite details, when you walk in the front door and you look up at the millwork and the level of detail of all the pilasters and then there are these carved wood panels above the closet and elevator doors on either side,” Fortman said. For Goldberg, who noted honoring the architecture and building a very authentic Prairie School residence was a new challenge for them, the team was fortunate to have the ability to work with all the beautiful materials, such as the four or five different species of wood and the artisan tiles from skilled hands like those at Motawi Tileworks of Ann Arbor, Michigan found throughout the home. “The millworker we worked with just did an incredible job of laying out these beautiful cuts of oak and then the stained glass and the handmade tile. The whole composition of all these beautiful materials was really an homage to crafts. Combining the tile and the wood and the oak floors and the stained glass was just a real luxury to be able to work with all these beautiful materials,” Goldberg said.

“The feel of the house from both the inside and out is very cohesive with the landscape and there is a lot of natural light and just a celebration of beautiful materials and the craft of making things. We did all the tile work ourselves and just the amount of detail it required and the time to install it was pretty intense and it was a great challenge for our tile setters. We were super proud of seeing all these beautiful materials coming together and to be able to realize the design in executing it, building the design, and seeing the vision come to life,” Goldberg added. The home is characterized by its illuminated interiors and extensive millwork, and accented by the vibrant green tile work in the foyer and fireplace surround, sunflower motifs in the sunroom, and backlit onyx panels with nickel inlays and a gilded ceiling in the powder room.

Defined by its rectilinear forms and geometric interpretation for the lakefront, the Prairie Style-inspired home reimagines an architectural language of the future, capturing the rhythm of sunlight against the drama of lake waters. Technical and sustainable elements are integrated into the artistry of the home, where inlaid gutters in the perimeter of the roof system are all but invisible, an underground pool vault provides out-of-sight storage for equipment, four geothermal wells sit roughly 400 feet below the driveway to help with heating and cooling efficiency, and photovoltaic panels are blended into the design in the roofing. Other elements of the home comprise distinctive lighting solutions and fixtures, such as the backlit panel of leaded glass in the sun room, LED lighting in the steam room to mimic a sunrise-to-sunset cycle, and a lower level complete with a spa area, potting room, gym and yoga room, kitchenette, home theater, billiard room, and a ’80s-inspired video arcade. “I think that it is the feel of the building, especially for people who understand architecture and construction, that it is a sum of all the parts,of all the efforts that went into all the details coming together as a cohesive sum of the parts. Being in the house and walking through, you get this sense of permanence and quality that is sort of an indescribable feeling that you have when you are in the building,” Goldberg said. “I also think it is important to recognize the clients, because the reason this project happened is because they really wanted to celebrate the Prairie School architecture and they were such enthusiasts about the project that they came to almost every single site meeting—and we had like 150 weekly site meetings. They were really a great part of the team. It wouldn’t have been possible without their interest and enthusiasm in creating the building in the first place,” Goldberg added.